Making a Soviet Murderer: The Case of Moscow Serial Killer Vasili Petrov-Komarov

Dr Mark Vincent investigates a scandal that shocked 1920s Russia

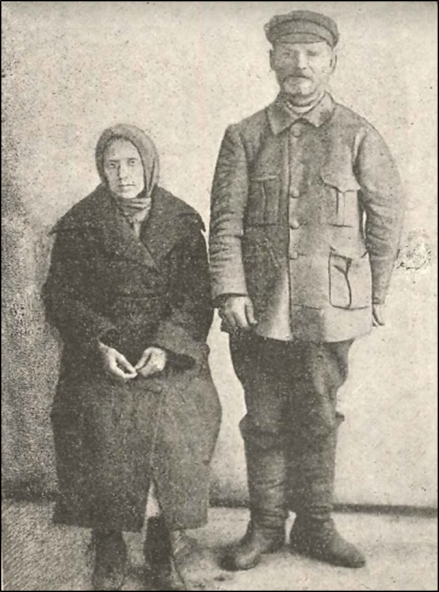

Photo credits: Mikhail Gernet (ed.), Prestupnyi Mir Moskvy (Moscow, 1924).

By 7th June 1923, anticipation had reached fever pitch in Moscow surrounding the imminent sentencing of Vasili Komarov and his wife Sophia, accused of murdering a combined total of 33 people between February 1921 and May 1923. These victims shared a number of common characteristics in that they were all male, all had a semi-rural background with an expressed interest in horse trading, and were all found in the vicinity of the city’s Shabolovka district with their limbs tied tightly together and packed into small sacks intended to disguise their size and shape.

In an early feuilleton, young writer Mikhail Bulgakov recalled how the case had captured the imagination of the public by describing how rumours circulated of pillowcases packed full of money and how Vasili would feed his pigs the victim’s intestines. Away from street-level gossip, the case also received the attention of the international news media through future Pulitzer Prize winner and controversial apologist of Stalin’s collectivization policies, Walter Duranty, a little over a year into his post as Moscow correspondent for The New York Times. Over the course of the twelve day trial, Duranty vividly detailed the protracted nature of the deliberations, moved from the regular court chamber to the Polytechnic Museum due to an ‘extraordinary interest’ in proceedings, and how the crowd broke into applause as Vasili and Sophia were sentenced to execution.

Proceedings depicted by Bulgakov and Duranty came at the culmination of a prolonged police investigation which narrowed in on the carriage driver after a large number of victims were found close to a twice-weekly horse market. Given that bodies were often discovered in the days immediately following trading, and that the sacks contained traces of hay or oats, further enquiries increasingly turned the spotlight upon Komarov who was identified as a regular attendee who appeared to do little business at the site itself.

Entering his property at 24 Shabolovka Street under the pretence of searching for an illicit brew house, detectives unearthed a corpse partially buried in a stack of hay in Komarov’s outside stable. Although the suspect was able to flee the scene through an open window, he was apprehended a few days later. Under interrogation, Komarov confessed without remorse to a total of 33 murders, 22 of which had already been accounted for. Five more bodies were discovered with the aid of his testimony and the remaining five had sunk to the depths of the Moskva River.

(Warning: The following paragraph contains a graphic description of murder; please skip to below the photos if you wish to avoid this.) An article published a year after the trial further detailed Komarov’s modus operandi, revealing how he would look to entice ‘peasants’ from the market to his apartment under the pretence of selling them a horse or other equestrian-related products. Upon the victim's arrival, Vasili would offer his prospective ‘client’ alcohol before producing a document for them to read while sat on a chair positioned in the centre of the room. While distracted, Komarov produced a hammer wrapped in a tablecloth and, approaching from behind, arched his arm around to strike them violently on the forehead. Suffice to say, this would knock his victim unconscious and, after letting their blood drip out into a bowl, finished the murderous act by strangling them with a noose. After initially stashing the bodies in a large chest inside his wardrobe, the corpses were later carried to a number of different locations on Shabolovka Street, including the derelict building next door and the grounds of a nearby mansion. Komarov’s pressing need to move the bodies further afield meant that he began transporting them to the nearby side street Konnyy Pereulok, then, using a horse purchased with money stolen from his victims, deposited them both on the embankment and in the Moskva itself.

The aforementioned article originated from an edited volume produced by the Moscow Bureau for the Study of Criminal Personality and Crime, an organisation originally instigated by a delegate of the Moscow Soviet and headed by leading criminologist Mikhail Gernet. Operating under the control of the Moscow Health Department, the Bureau rejected elements of Lombrosian-based atavism in favour of understanding criminality through conditions of time and space.

The article therefore wove the Komarov case around the main themes of the volume, which emphasised the primacy of the urban environment, to the point of excluding any mention of the outside stable, and argued how Komarov’s relationship with alcohol (influenced by his parents and older siblings) was seen as ‘preparing the soil’ to be further cultivated by the ‘legalized murder’ of warfare. This was in reference to Komarov’s involvement in the First World War, in which he reportedly rose to the rank of general and authorised his own battalion to shoot a spy while also taking part in a vote to execute a captured enemy soldier. When later detained himself, Vasili had the foresight to change his surname from the original Petrov to avoid being killed (he is referred to as ‘Petrov-Komarov’ throughout the Moscow Bureau chapter but only ‘Komarov’ in reports elsewhere).

This issue regarding Vasili’s name shows one of the ways in the Moscow Bureau ‘Sovietized’ the Komarov Case to align it with their attempt to shift focus away from ‘celebrity’ individuals and toward a study of the unnamed criminal masses. Referring to the subject as Komarov-Petrov and excluding his nicknames (formed using bestial epithets such as the ‘Wolf of Moscow’ or the ‘Human Wolf’) took away a degree of Vasili’s individuality and played down the more sensationalised aspects of the case. This was also achieved through a discrepancy in the number of murders, with the Moscow Bureau chapter revising the number down to 29 as opposed to the 33 cited elsewhere.

Alongside this, the virtual absence of his wife Sophia despite the focus in the Bureau’s wider writings on the increase of female crime, and that she was also sentenced to the death penalty as his accomplice, remains a curious omission which can only be explained in that her inclusion would suggest the existence of traditional, patriarchal structures and dispute the arguments expressed elsewhere. While their approach shows that the Moscow Bureau were adjusting their language in an attempt to speak ‘Bolshevik’ this clearly came into conflict with the details of the case. Unlike the seemingly irrefutable evidence pointing toward Komarov, unravelling some of these wider contradictions may bring us closer to understanding the role of criminologists and the study of crime and punishment in the early Soviet state.

Dr Mark Vincent

School of History, University of East Anglia

@VincentCriminal