The possibilities of freedom - for Soviet toys in a Moscow kindergarten...

Paweł Wargan describes the historical and personal roots of his debut film

Nevalyashka - a sort of Soviet weeble - among other Soviet toys. Image credit: Museum of Soviet Childhood

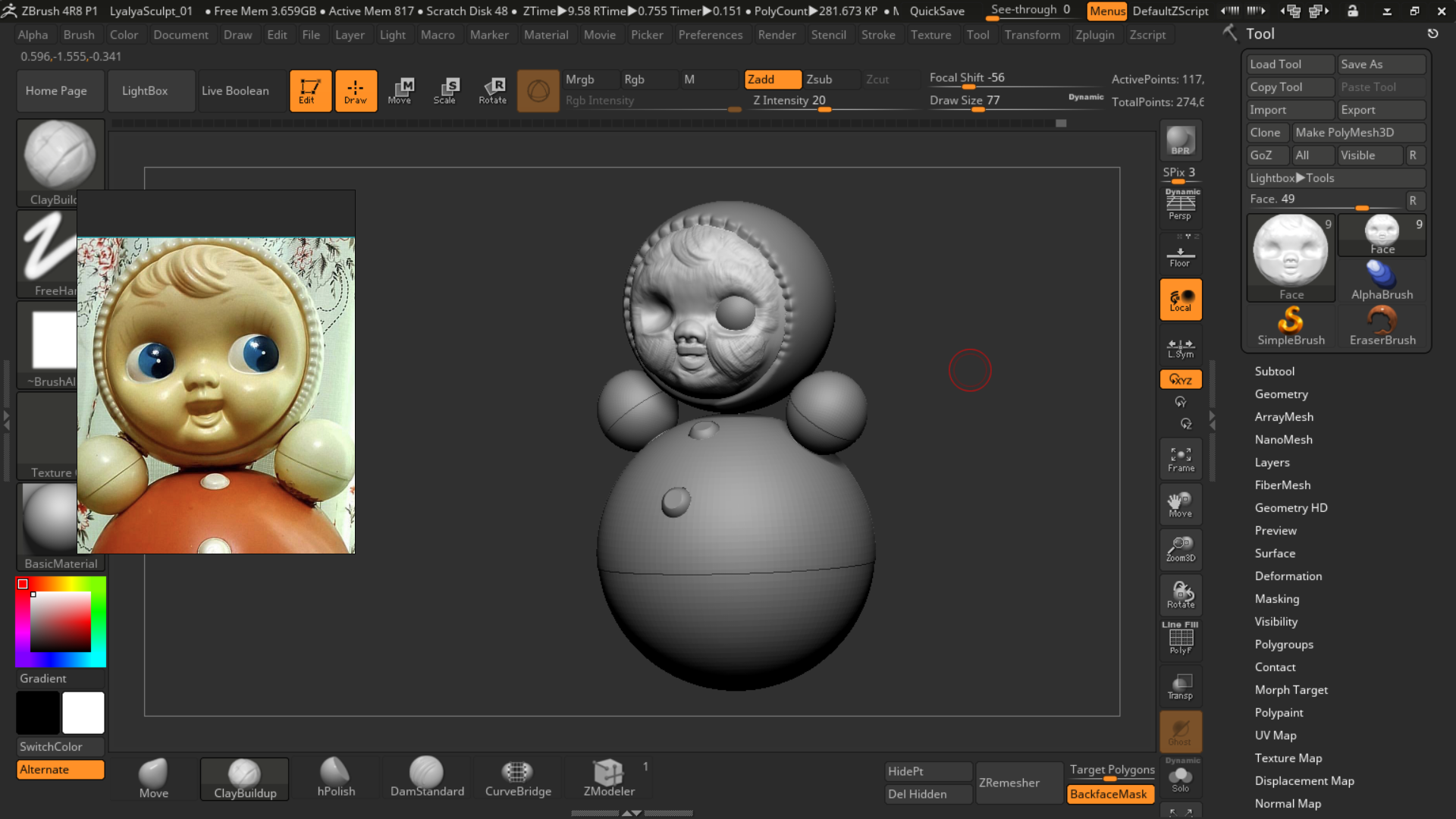

Rendering image for the character of Lyalya, from A Soviet Toy Tale

Near the end of A Soviet Toy Tale, an animated short that I am co-creating with my partner Kristina Lanis, a kindergarten teacher decries the violence dealt upon her classroom by the rising tide of lawlessness that accompanied the collapse of the Soviet Union. “We were promised freedom,” she says. “But all we got is freedom from responsibility” — to which her colleague, equally embittered by the “hooliganism” and “anarchy” of the early 1990s, responds: at least they got Coca Cola.

There are no staunch free-marketeers on the production of A Soviet Toy Tale - and I suspect that, in the Moscow of 1991, there were fewer than we like to imagine. In the romanticised, prevailing Western narrative of that time, the collapse of the Soviet Union came as a liberation. It was the final trickle from the Red Iceberg — as a piece of McCarthy-era propaganda called it — that ended history. A whole industry emerged to study the spectacle of Russian failure and its Western sprouts. It became rhetorical fodder for those who believe that, to quote the Iron Lady, “there is no alternative” to the illusory freedom of a deregulated market economy. Then all that was apparently interrupted by the rise of a pasty-skinned, quietly intransigent KGB apparatchik who allegedly acquired a video tape of the American President wetting the bed…

We asked the toys what it means to be free, and how much work goes into finding that freedom

All this Western pining for easy explanations ignores the very real suffering the Soviet Union’s collapse inflicted. Now, as our own political moment pushes a generation into rediscovering the possibilities of socialism — possibilities that died in the Gulag; in Prague in 1968; and again, in Moscow in August 1991 — it feels right to revisit the moment at which the Soviet Union crumbled. What, really, was lost? What, if anything, should be salvaged?

Kristina and I came to the film through our own experience of Soviet-style expropriation. In 1995, I brought my favourite toy truck to a boxy concrete kindergarten in Gdańsk, Poland. At the end of the day, I tried to take it back, only to be accused of theft. My parents were dismissed as accomplices when they came to my defence. I never went back. Kristina didn’t either, after a similar experience in a Moscow kindergarten some three years after mine. We were in Bangkok when we discovered that our distaste for authority had the same origins. Then the story wrote itself — we had to know what our lost toys would say if they could speak.

So, we pushed onto our toys the entire weight of our creative and political anxieties. We asked them what it means to be free, and how much work goes into finding that freedom — yearnings that increasingly collide with the realities of the lived world. You see, it’s not hooliganism that trashes the teachers’ classroom at the end of our film — it’s the toys’ battle over the future of their world.

Rashka (voiced by Yana Lyapunova), a big-eyed soft toy, wakes in Kindergarten No. 1678 in Moscow to find that she had been stolen from her Masha by the kindergarten teachers. She learns that she is not alone. Other toys had also been taken over the years, condemned to seeing their rightful owners in the kindergarten each morning, but unable to go back home. Together with Gagarin (Victor Averyanov), Commander (Igor Pavlovs) and Pruzhinka, Rashka plots to escape.

But as they devise their plan, Stamp and Spravka (literally, a stamp and permit, the former voiced by Liza Mircheva) insist that the escape be rubber-stamped by the authorities. The other toys — a group of American-made chess pieces and a Yeltsin Russian doll — take a stand against the bureaucratic power-duo. And as our protagonists try to escape, the toys re-enact the events of August 1991 in Moscow, in which a group of Communist hard-liners tried to unseat General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev by staging a coup in Moscow. Things get bloody.

Svetlana Alexievich, the Belorussian writer whose collected accounts of that era earned her a Nobel, writes about the failed coup in Second-Hand Time. Marshal Sergey Akhromeyev, one of its backers, left five neatly-stacked handwritten notes on his Kremlin desk before hanging himself from the radiator. “I cannot go on living,” he wrote in one, “while my Fatherland is dying and everything I heretofore considered to be the meaning of my life is being destroyed.” Alexievich then speaks to an unnamed Kremlin insider, N., who tries to make sense of the suicide. “He saw the young predators stirring… the pioneers of capitalism,” N. says. “Instead of Marx and Lenin, they had their minds on dollars.” The discovery of money, another interviewee says, “hit us like an atom bomb.”

None of this is to rehabilitate the Soviet Union — a regime that murdered tens of millions of its own citizens and usurped the power that it promised to spread. But it does question whether the history of the 20th century has really been written in stone.

Look, our film is about toys. It’s silly. It’s short. It pits an evil nevalyashka against a plastic Gagarin that was once made for a competition in Detskii Mir. But by going back to the drawing board (really, the 3D modelling software), we found an opportunity to delve into the convulsions of a place in transition. To take the past and collide it with the future. To channel that something in the Russian spirit that, as Alexievich said in her Nobel Lecture, “compels it to try to turn… dreams into reality.”

Our film will be out next year if we raise the money in the next few months (if you are sitting on a pile, please get in touch). Hopefully, it might make a small dent in the telling of a history that is still being written.

About the author:

Paweł Wargan is a filmmaker, writer, photographer, and policy adviser. He is the writer and director, with Kristina Lanis, of A Soviet Toy Tale.