Nijinsky on Nijinsky: the Decline and Fall of the Ballet Russes

Vaslav Nijinsky, once the star of the Ballet Russes and Sergei Dhiaghilev’s personal favourite, fell from grace with a heavy thud. A dancer and choreographer of phenomenal talent, Nijinsky left a legacy not just through his work, but also through his diaries, written in the years after the end of his career, as his lifelong battle with mental illness intensified. Pippa Crawford takes a look at this complicated figure.

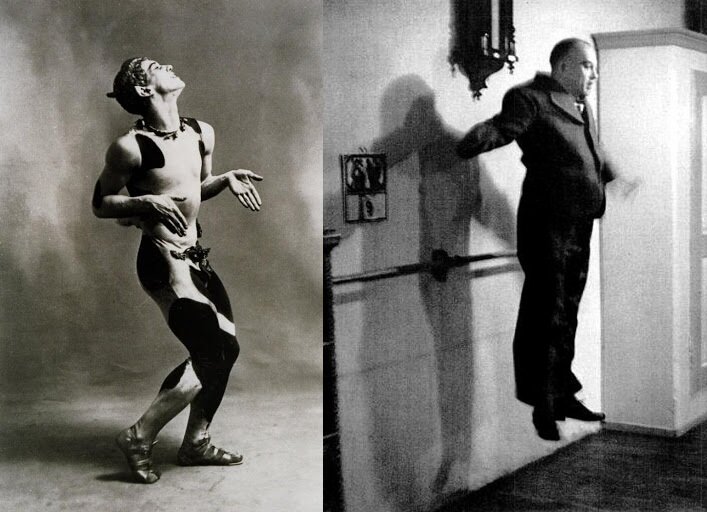

Left, Nijinsky as the Faun in Afternoon of a Faun (1912). Right, Nijinsky reprises his famous jump in a Swiss sanatorium, in a controversial photoshoot for Life (1939).

In true idol style, Vaslav Nijinsky is remembered by one name alone; the world knew him as ’the God of Dance’ while Vaslav himself has remained an enigma. Born in 1889 into a family of Polish dancers and circus performers, the young Nijinsky could jump so high into the air that he seemed to hover there. He would dance ‘like a girl’ – dancing en pointe was almost unheard of for a male dancer of his era; he would dance with his feet turned out, hammering the stage at terrific speed; he invented his own steps and his own rules; he was thrown out of the Petersburg Imperial Ballet School. As a student he attracted the attention of the critics and as principle soloist of Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes he swiftly became one of the most distinguished dancers of all time. The nomadic troupe took their first steps in Paris in 1909, a period when ballet was on the decline in western Europe. Glamourous and highly trained, Diaghilev’s dancers created a great stir. It was in Paris that Nijinsky starred in the infamous 1913 premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. A combination of the strange, disjointed music and the primal sexuality of Nijinsky’s choreography split the audience (which included Ravel, Debussy, Picasso and Gertrude Stein) into two warring factions who shouted insults and attacked each other with umbrellas and chairs. The dancer brought a host of diverse characters to life, notably the puppet Petroushka, the androgynous Spirit of the Rose and the carnal Faun. Variously worshipped and derided, but never far from the headlines, Nijinsky took on Europe, then the globe.

“I danced frightening things,” Nijinsky writes, “everyone was afraid of me.”

Nijinsky and Diaghilev in Nice (1911). Image credit: The Genealogy of Style

Sadly, it was not to last. Following his break with the Ballet Russes in 1917, Nijinsky’s mental state began to deteriorate and the star spent the last thirty years of his life in and out of psychiatric hospitals. Between 1918 and 1919, Nijinsky was stranded by the war in a villa in St. Moritz with his wife Romola de Pulszky and their infant daughter. He occupied himself during this period by writing a diary, which runs to four notebooks in its unexpurgated form and remains one of the only autobiographical accounts by a major artist living with schizophrenia. Despite the dedication of his youth to physical training and choreography, there are few references to dance to be found here. Instead, Nijinsky’s everyday concerns and grandiose delusions are interspersed with a tentative attempt to come to terms with the abrupt end of his life under the spotlight, his own identity and that of those who shaped it. “I danced frightening things,” Nijinsky writes, “everyone was afraid of me.”

There is something inescapably voyeuristic about reading someone else’s diary and Nijinsky’s vulnerability at the time of writing complicates things further. Long passages deal frankly with the dancer’s confusion over his bisexuality, his visits to prostitutes in Paris and his preoccupation with bodily functions – required initially by his work, but continuing for years into his retirement. Nijinsky threatened to shoot anyone who looked at his notebook, yet was also keen for for his uncensored diary to be published in his lifetime. The text is peppered with wild inconsistencies of this kind. Although clearly the work of a troubled individual, sections such as Nijinsky’s ongoing quest to patent the perfect fountain-pen (named God, after himself) remain uncomfortably funny – and closer, perhaps, to the outrageous ideas he was hailed for in his prime. The prose is stilted and repetitive, teeming with odd tautologies and non-sequiturs – “Journalists who write nonsense are money,” – and veering into broken syllables, obscenities and bilingual puns which don’t quite work. Whether despite these things or because of them, other passages remain profound. “To understand does not mean to know all the words,” writes Nijinsky. “Words are not speech. I understand speech in all languages.”

A page from Nijinsky’s diary (1919). Image credit: Russian Art & Culture

In the diary’s most striking passages, Nijinsky touches on his relationship with the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballet Russes. Diaghilev was a charismatic figure, both a creative visionary and a shrewd business operator. He was also notorious for seducing his young, often impoverished male stars; troubling from a post-Weinstein perspective and troubling to Nijinsky at the time. In 1908, Nijinsky was introduced to Diaghilev with the encouragement of his own mother. He was nineteen years old. The diary records: “I found luck there because I immediately made love to him. I hated him, but I put up a pretense [sic] for I knew that my mother and I would starve to death.” Nijinsky was hired. During the heyday of the Ballet Russes, he and his patron were to clash many times. Nijinsky’s directions became increasingly difficult to understand, let alone realise; he once drove the classically-trained Lydia Sokolova to tears during a rehearsal by ordering her to move ‘through’ the music instead of ‘to’ it. Diaghilev racked up debts and scandal wherever he went and his charge began locking his hotel room door at night to keep him out. In 1913, Nijinsky married Romola – a Hungarian socialite who had pursued the Ballet Russes throughout their South American tour. As Nijinsky and Romola shared no language except French – hers fluent; his broken – and the dancer’s tastes inclined more strongly towards men, one suspects an element of desperation on both sides. Distraught, Diaghilev fired him. Unlike most of his friends and colleagues, Nijinsky didn’t see this coming; in a telegram to Stravinsky from this period, he begs the composer: “Please, could you ask Serge what the matter is?”

Nijinsky and Romola (1916). Image credit: My Retro Photo

Nijinsky struggled to manage his career after leaving Diaghilev, partly because, as the impresario’s former favourite, he had effectively been paid in pocket money and had never signed a formal contract. The diary charts both Nijinsky’s contempt and lingering admiration towards his benefactor, noting: “Diaghilev has a lock of hair dyed white at the front of his head. Diaghilev wants to be noticed. His lock of hair has become yellow because he bought a bad white dye [...] In Paris I began to hate him openly,” but also “I loved Diaghilev sincerely,” “I know everything about him.” As Nijinsky’s health further deteriorates, his diary becomes more and more disjointed, at times repeating: “Diaghilev is an evil man,” while at others: “I do not want people to think that Diaghilev is a scoundrel and that he must be put in prison. I will weep if he is hurt.” Thoughts of the impresario bleed into all areas of Nijinsky’s new life: “All Diaghilev’s smiles are artificial. My little girl has learned to smile like Diaghilev. I have taught her because I want her to give him a smile when he visits me.” Nijinsky’s diary makes few concessions to time or place – the director remained for him firmly in the present tense. The last notebook, written in the form of unsent letters, contains one for Diaghilev addressed simply to ‘Man’: “Don’t think I don’t listen,” he writes, “I am not yours. You are not mine. I like declining you. I like declining myself. I am yours. I am my own.”

Nijinsky’s story has undeniably been told many times, but its melodramatic events make it tempting to fall back on the old romantic clichés: the mad artist, the misunderstood artist, the suffering artist under the thumb of the rakish Svengali. The damage began in Nijinsky’s lifetime, with the publication of Romola’s censored edition of the diary (which removed explicit passages and all the unflattering references to herself) and a spate of inaccurate biographies by well-meaning friends. Upon the diary’s full publication in 1999, some argued that overemphasising the mundane or shocking details of Nijinsky’s personal life could distract from the brilliance of his achievements. Yet apart from a few photographs, Nijinsky’s diary and letters are our only way to glimpse the man as an individual as well as an artist.

Nijinsky in ‘les Orientales’ (1911). Image credit: Russian Art & Culture

It’s still possible to view the exotic costumes designed for the company by Goncharova and Bakst, marked by the sweat of the performers. Stravinsky’s riot-inducing score is just a couple of clicks away and we can see fragments of Nijinsky’s own choreography performed by other dancers. But no film exists of Nijinsky dancing at all – the artist insisted that the shaky camerawork of the period could not do justice to his troupe. With the colour and cacophony of the Ballet Russes all but absent, the diary lends us a starker viewpoint onto Nijinsky’s later years. However, it has also led to a more nuanced understanding of his life and work, which culminated fittingly in a range of theatrical tributes. At the Edinburgh Fringe in 2015 Nijinsky’s Last Jump fused past and present, showing the institutionalised dancer reliving his former performances. The Australian Ballet’s 2016 production Nijinsky! revisited his fraught relationship with Diaghilev. In the same year, Letter to a Man, starring Mikhail Baryshnikov, placed the diary itself at centre stage. These and further productions honour the talent that set Nijinsky apart from his contemporaries, yet simultaneously acknowledge his flawed behaviour, his mistreatment by others – as well as the boredom of much of his life, the long periods of illness, isolation and self-doubt. Considering the collect-and-discard nature of contemporary celebrity culture, this seems more important than ever.

In 1929, Nijinsky received a letter from Stravinsky, which places him back in the centre of the world he left behind. “My dear Vaslav,” begins the composer, “I am writing to you on the occasion of the recent death of our dear colleague, Sergei Diaghilev. It seems that this event has stirred in me a certain nostalgia for the collaborations in which we all participated together.” Stravinsky writes with affection for his friend, informing him that his sister, Bronislava Njinska, has continued his legacy, becoming a respected choreographer in her own right. The letter ends poignantly: “In closing, I thank you once again for the work that you continue to do, and I pray blessings on the rest of your career.”

Vaslav Nijinsky never performed again. Only through his own voice, with all its discords, can we recapture the compulsive rhythm of his life and dance.

Mikhail Baryshnikov as Nijinsky in Robert Wilson’s ‘Letter to a Man’ (2016). Image credit: Robert Wilson

Suvretta House, the St. Moritz hotel where Nijinsky gave his last public performance in 1912. Image credit: Suvretta House

Pippa Crawford (@crawford-pippa) is a freelance critic and student of Russian Studies at University College London. Currently studying at the Higher School of Economics, St. Petersburg, Pippa likes travel and translation and loves drama. She also enjoys watching plays.