Moscow under Siege Again

Blog by Clem Cecil (@Clemochka), Director of Pushkin House, co-founder of the Moscow Architecture Preservation Society and former Director of SAVE Britain's Heritage

This piece was commissioned by the BBC Russian Service.

This weekend - 14th May, 2017 - huge protests are expected on the streets of Moscow - a march against the biggest demolition programme in history. A new bill is presently under consideration in the Duma that that will remove some 10% of Moscow’s housing stock (7,900 buildings) home to 1.6 million of its 12.6m population. It is aimed principally at the 5-storey apartment blocks built under Nikita Khrushchev in the 1950s otherwise known as pyatietazhki or khrushchevki, but also appears to be arbitrary, allowing the demolition of anything that the city wishes. The proposals have sent shock waves through Moscow and led to the formation of extremely organised and articulate action groups such as Snos Domov Info.

This week at Pushkin House, ex Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov had this to say about the demolitions that he oversaw of the same kind of housing stock during his 18 year tenure until 2010. He demolished about half the amount over the last ten years of his time as Mayor.

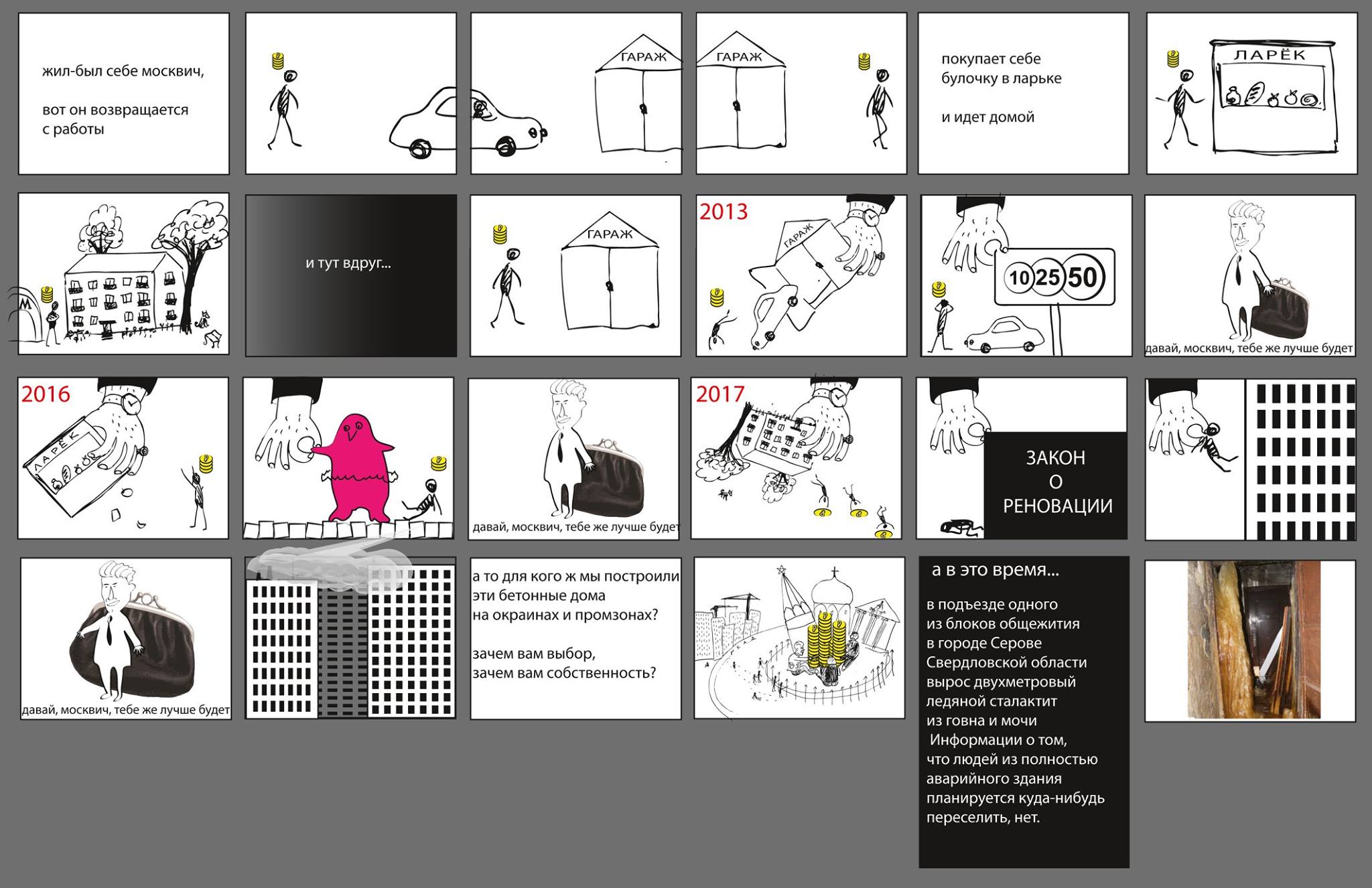

Campaign poster against proposed demolitions in Moscow

The demolition plans are almost as ambitious as the original building project itself, that provided housing for tens of millions of citizens, across the entire USSR. The Khrushchev housing project was a modern marriage of technology and socialism: free housing provided for all. Between 1955 and 1964, roughly a quarter of the Soviet population, some 54 million people, received their own flats. They were built without lifts, to speed their construction, and were intended to provide individual apartments for a populace that had been crammed into barracks, communal apartments and other forms of inadequate housing where bathrooms, if they existed at all, were shared, as were kitchens. Although quickly nicknamed Khrushcheby - combined from the words Khrushchev and trusheby (slums) - people were delighted to move into their own private apartments. Arguably, at these kitchen tables people were able, for the first time, to formulate and discuss their individual opinions about state policies, and thus began the erosion of the might of the Soviet Union from within.

'Splashing Pool with a hillock.' Courtyard No.5. From 'The 9th Quarter. Experimental-model construction of a residential quarter in Moscow.' Moscow 1959

Today’s bill represents another kind of erosion: of the rights of citizens to their own property, as not only was there no meaningful consultation, but also the bill includes a clause forbidding legal recourse for those wishing to defend their apartments. Citizens have been promised new apartments that will be up to 20% bigger (the kitchen and the corridor, not the other rooms). No financial support is being offered for the inconvenience of moving.

Ironically, one of the co-authors of the bill is Vladimir Resin, deputy mayor under Yuri Luzhkov, who initiated a similar programme on a lesser scale, demolishing some 1,7000 Krushchev-era residential blocks over the last twenty years, and their replacement with high-rises. He fondly remembers in his own memoir “Moscow in Scaffolding” his own family moving into their own apartment during the Krushchev period, and having their own bathroom for the first time. Mr Resin now owns a capacious dacha with 10km of grounds.

From 'The 9th Quarter. Experimental-model construction of a residential quarter in Moscow.' Moscow 1959

One of the hallmarks of the Krushchev-era micro-regions, as they are called in Russian, is that they were carefully planned, with all the necessary facilities: a market, shops, a metro station, acinema, roads and green spaces. They were thoughtfully laid out and well-planted, with trees now as high as the 5-storey buildings. Today these are well-established areas where people happily live. Not all, but many of the buildings are in good condition and there is no indication in the plans for how poor the condition of a building has to be for it to be demolished, or whether a survey will be undertaken to establish this fact.

In his statements, Mayor Sobyanin implies that because the Communism of the future that Khrushchev promised never happened, it is time to tear down the temporary housing that was built during the period, and make way for something more permanent that will ‘last for 100 years’. After all, is the implication, we are now we now find ourselves in a stable new era of capitalism. Cue- hollow laughter.

Moscow has very unusual laws pertaining to the ownership of land which mean that since the collapse of the soviet union, when all land belonged to the state, nobody has taken responsibility for common areas. Today, you can own your apartment, but not the land under the apartment building. The land under the building is owned by the city and the land between housing blocks is owned by the municipality or the developer. They have no responsibility to create pleasant urban spaces, and they rarely do.

'Alcove in a common room.' From 'The 9th Quarter. Experimental-model construction of a residential quarter in Moscow.' Moscow 1959

Campaigners are concerned not only about losing their apartments, but also their pleasant and in many cases well-functioning urban environment. Observing the shockingly indifferent response of Duma Deputy Mikhail Degtyarev, one of the authors of the bill, in an interview on Rain TV station, to basic questions about how it will be implemented, one is struck by the lack of consideration for the human element. In a discussion on TV Radio Svoboda with anchor Sergei Medvedev, urbanist and sociologist Petr Ivanov, mentioned another bill that had been passed in february that he thought was more significant, but that this new bill, is a cover for it. He said this bill is, "a pre-election cover-up for the real essence of the other bill: that the powers that be receive the right to mark off territory and name it a renovation zone. In the framework of this renovation zone they can demolish whatever they want and build whatever they want... they can introduce their own construction norms and rules. A zone is constructed in which the normal laws of the country do not apply." Sergei Medvedev concluded the discussion by dubbing this approach to the city: ‘authoratitive urbanisation.'

Artists and Activists MishMash create their own protest-wear, Moscow 2017. "Instructions: photograph your house, find a printers that 'prints on t-shirts' with full coverage. Sometimes it is called '3D t-shirts'. Upload your picture and place your order. And that's it! You have something to wear!" #мынесносны

Not considering the human element in large-scale demolition and construction schemes is folly. After working in conservation and campaigning in Moscow for 8 years, I moved to SAVE Britain’s Heritage where one of the lead campaigns was opposing Pathfinder, otherwise known as Housing Market Renewal. It was introduced by former Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott in 2002, when 12 northern cities bid for the right to enormous government subsidies to demolish up to 400,000 terraced houses to be replaced by new and bigger housing with bigger gardens and garages to appeal to wealthier buyers. Like khrushchevki, terraced housing, almost 100 years earlier, were built to house growing worker populations moving to the cities to work in factories and moving them out of slums, and as with the Krushchevki, the houses and rooms were considered too small. And also similarly, there was very little public consultation. The scheme blighted thousands of lives of people fighting to stay in their homes; it divided neighbourhoods where some wanted demolition and others didn’t; it blighted huge areas of housing which were emptied of their inhabitants and ‘tinned up’ awaiting demolition. When demolition was blocked and hampered due to mismanagement by local councils or legal cases from inhabitants wishing to save their homes, areas simply declined and became wastelands.

In the end fewer than 30,000 houses were demolished, and replaced by less than half that number, at the cost of £2.3bn, subsidised by the government. Last year the winner of Britain’s biggest art prize - the Turner Prize - were Assemble design studios for designs to adapt simple terraced housing for modern needs. This was a clear indication of changing attitudes towards the terraced house.

What Pathfinder demonstrated was that if the human element is not considered it leads to huge wastage of resources both in terms of housing stock (embodied energy) and money. It also leads to divisions within neighbourhoods, thousands of blighted lives, and large inner-city areas becoming demolition and building sites for many years.

Assemble Studio's winning designs for the rehabilitation of Granby Four Streets through sensitive renovation

Assemble Studio's winning designs for the rehabilitation of Granby Four Streets through sensitive renovation - interior - creating a garden out of ruins.

Granby Four Streets, Liverpool, blighted by Pathfinder, otherwise known as Housing Market Renewal

A demolition programme and reconstruction programme of the ambition and scale proposed in Moscow is going to lead to a massive grassroots protest movement, people joining their voice to the dalnobioshchiki and others protesting at the moment.

There already appears to be an element of back-tracking: Sobyanin recently announced that there would be further consultation before the final proposed list of demolitions was announced on 1st May. It is important to point out that not everyone thinks that the bill is bad news. Some people’s housing is in an extremely poor state. Architect Andrei Kaftanov, specialist of this period of architecture believes that “this bill is an important political statement that makes us think about what to do with Soviet era housing, which is a good thing and necessary to think about.” Kaftanov points out that poor housing is not all from the Khrushchev era, and includes 12-18 storey buildings from the Brezhnev era.

Acknowledging that although this will probably affect between one third and a half of Muscovites, he thinks that if approached properly, real enhancements to the city are possible. ‘The approach has to be surgical,’ Kaftanov says. ‘With careful intervention it is possible to improve housing and urban areas in such a way that fewer people are displaced and there is an overall improvement of the urban environment.’ However, with reference again to Pathfinder, developers, whether that is the government or private investors, often want large, convenient rectangular sites on which to build, mercilessly knocking down whatever might get in their way, with little regard for the wider neighbourhood.

The economics of this plan are another issue. Unless the government has billions, nay trillions of spare roubles splashing about, this can only be delivered with private developers coming on board. However, the housing market in Moscow has slowed right down, so it is doubtful that there would be an appetite to build thousands of new flats, especially when a significant proportion of them will not be for sale, but rather are replacing demolished apartments.

There is another way: in Eastern Germany, as Guardian journalist Alec Luhn pointed out in his excellent article in March this year, some Khrushchevki were refurbished by Stefan Forster. This may not be possible across the board but it it certainly possible in many cases. This involved removing the top storey, as “a commitment to higher quality through reduction”, knocking apartments into each other and adding balconies and lifts where possible. It is also essential to have clear criteria for which buildings are to be replaced and why. It should be done in stages, and not in one tsunami of destruction and should be thought of as a whole with the entire city - how new high rises around the edge of Moscow will affect the whole city. If this goes ahead we will all remember the Moscow of today as a quaint old capital, with skies of scudding clouds.

It was established by British architects Peter and Alison Smithson in the 1960s that 6-storeys in the optimum height for a residential building - 6 storeys up you are still close enough to the ground to feel part of the city and connected to the whole. The theories of American urbanist Jane Jacobs, republished in recent years in translation in Russia, about safe neighbourhoods hinge on them being low-rise - 6 storeys and less - allowing people to keep an eye on what is happening on the street. This project carries a very real danger of disconnecting hundreds of thousands of muscovites from their own reality and from the reality of the city. Beyond the replacement of some of the worst housing - that constitutes only a fraction of the some 8,000 buildings currently proposed for demolition - it is hard to see what positives this will bring. On the contrary, it has the potential to cause huge suffering and be a major distraction and burden on the lives of Muscovites wishing to remain in their homes.