In the early years of the Cold War, the skyline of Moscow was forever transformed by a citywide skyscraper building project. As the steel girders of the monumental towers went up, the centuries-old metropolis was reinvented to embody the greatness of Stalinist society. Moscow Monumental explores how the quintessential architectural works of the late Stalin era fundamentally reshaped daily life in the Soviet capital. Drawing on a wealth of original archival research, it examines the decisions and actions of Soviet elites—from top leaders to master architects—and describes the experiences of ordinary Muscovites who found their lives uprooted by the ambitious skyscraper project.

Moscow Monumental is published by Princeton University Press.

FIVE MINUTES WITH KATherine zubovich

Katherine Zubovich is assistant professor of history at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York. Her interests include the history of cities and urban planning; the history of architecture and visual culture; and modern transnational history. She received her PhD from University of California, Berkeley, and previously studied at the University of Toronto and the University of Victoria.

What explains your interest in Russia?

My undergraduate major was in art history but I wound up in my second semester taking an introductory course to the Russian language and from then on I was hooked and signed up for any other course that could fit into my schedule: Russian language, Slavic literature, Russian and Soviet history, a class on Russian constructivism. It culminated in taking my final semester in St Petersburg, which was my first experience in Russia and cemented my interest, ahead of a Masters and a PhD. I happened to marry someone from the former Soviet Union, but I don’t have any family connection to the region myself.

What is your book about?

Monumentalism and its consequences: it’s a comparison between the ideal city designed on paper and the complexity of the real city and all its moving parts. The construction of skyscrapers in Stalinist Moscow displaced large numbers of residents while rewarding elites with lovely new apartments. The buildings were supposed to communicate the permanence of the Stalinist regime and victory in the war, but they were also destabilising forces.

Why did you decide to write it?

I was interested in thinking spatially and architecturally about the Stalin era. Once I’d narrowed down my focus to Moscow, the topic of the Stalinist skyscrapers became obvious. The buildings stand out really prominently and still serve as landmarks today, but very little archival research had been done. I did a scouting trip and found that there are really rich sources: not just architectural and bureaucratic documents but all kinds of sources that allow us to peer into the social, cultural and political lives of these buildings to grapple with their effects on the city and its inhabitants.

What were the residents’ reactions?

One category I pay particular attention to are those who were displaced to make way for the buildings. They were concerned that the housing they were living in, and was about to be demolished, was in quite a bad condition. But there was also a real frustration that most were being resettled on the outskirts of Moscow and in effect were being deurbanised. There was a real premium in the Soviet Union on urban culture. To take groups of Muscovites and place them in the outskirts was humiliating and frustrating. It implied a loss of social status and a lack of access to amenities like doctors and schools.

Was it dangerous for people to complain?

Yes and no. A lot of complaints were about middle managers, and top officials were eager to learn about corruption, such as giving apartments to relatives. There is a sense that in inviting these kinds of letters, the late Stalinist state was opening the door to people’s real disillusionments - of promises unfulfilled, living in this great Communist country when the reality is that most were in crowded communal housing. What surprised me was that state officials followed up in a semi efficient way - routing complaints to other offices and following up.

How would you contrast the approach with urbanisation in the West?

The construction of skyscrapers in Stalinist Moscow is similar to what we would call in the US and the UK urban renewal, slum clearance - these were projects that displaced and tore apart large communities, including with highways construction, and were portrayed in the West as a public celebration of ridding the world of urban blight. In the Soviet case, I didn’t find that same kind of popular rhetoric. There was real resistance after 1945 to talking publicly about urban demolition, and much more emphasis on new buildings.

What was the attitude to US skyscrapers?

In the 1930s in planning the Palace of Soviets, which was never built, we see interactions between Soviet architects and engineers and their American counterparts. There was a technological exchange and in the US during the Depression there was interest in working in the Soviet Union. In the post war years, the connection was really fraught and trips were no longer possible. The Russian word for skyscraper was not used publicly when discussing Moscow’s new tower - skyscrapers were for capitalist countries. The message from Moscow was that they were improving on skyscrapers: rather than having Manhattan buildings crushed together, blocking the flow of air and light, Moscow “tall buildings” were spaced out one from another in a rational way and connected to larger architectural ensembles with boulevards and developed river embankments. There was this idea that the vysotki were the pinnacle of tall building construction.

Did the USSR promote its architecture abroad?

This was Socialist realism’s heyday - after the influence of American skyscrapers in 1930s, now the Soviet ones would come to the fore, with Soviet structures to be exported along with communism. There was funding devoted to duplicating Moscow skyscrapers in other cities and design expertise. The architect of the Moscow State University worked on the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, incorporating Polish national features into an otherwise Moscow-like tower. There were others built in Bucharest, Riga, Kiev and Prague. Now in Astana, there is an afterlife to this with a post-socialist vysotka built in the 2000s.

What most surprised you in your research?

The effect that these buildings had beyond themselves. My research started with 8 points on a map for the 7 skyscrapers built and one not built. After a few months in the archives, I was exploring dozens of other points. I didn’t expect to find they had this outsized effect on the city as a whole. It required a whole infrastructure, the supplies, housing for the construction workers. Moscow as a whole was involved.

What is your next book about?

It’s a history of Soviet visual statistics - we’d call it data visualisation today. I’m interested in how Soviet artists and economists starting in the 1930s worked together to take what were very complex economic and planning ideas and goals and transform them into simplified images that could be understand by any and all Soviet citizens. Images were circulated on posters and in books to celebrate, say, the achievement of the five-year plans, or of the USSR vis a vis the West.

INTERVIEW FOR PUSHKIN HOUSE BY ANDREW JACK (@AJACK)

RELATED EVENT: The aesthetics of power

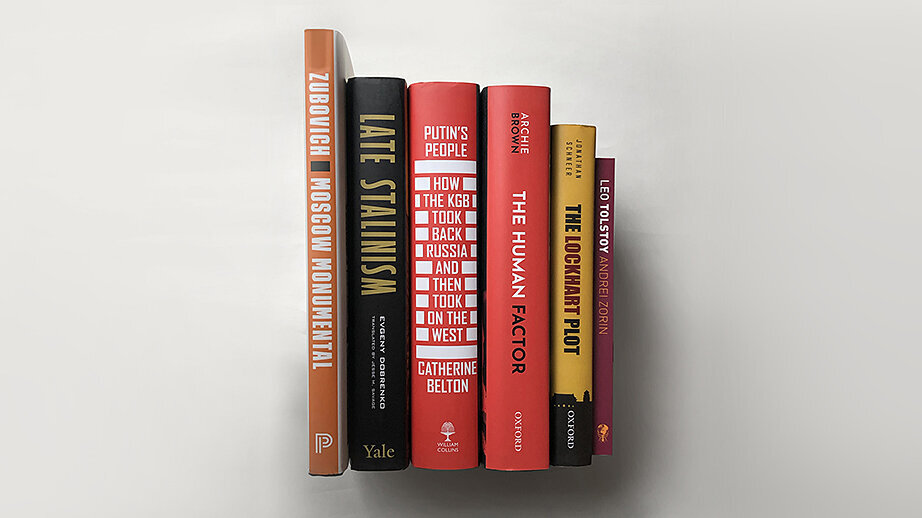

Want to learn more? Katherine Zubovich, author of Moscow Monumental, will be in conversation with fellow book prize 2021 nominee Evgeny Dobrenko, author of Late Stalinism, at an online event on 29 September at 6pm BST. The pair will be joined by Michał Murawski, an anthropologist of architecture who has a special interest in the impact that communist-era built environments continue to exert on the capitalist cities of the 21st century.

reviews

"Impressive detail"—Anthony Paletta, Literary Review

"Zubovich has done stellar work in the city’s archives, uncovering a trove of letters and petitions from ordinary Soviet citizens. . . This is a book which delves into the very human tensions created by a society forced into transition, and the effects on a city undergoing a seismic political, cultural, and architectural change."—Jennifer Eremeeva, The Moscow Times

"Moscow Monumental is a significant study of one of the most important building campaigns of the early Cold War and the impact it had on the urban life of the Soviet capital."—Richard Anderson, University of Edinburgh

"Zubovich offers unrivaled insight into how Stalin's skyscrapers have shaped Soviet memory and identity while shedding new light on the era in which they were born—one where global monumentalism brought us Rockefeller Center and the Golden Gate Bridge. Engagingly written and well documented in photographs, Moscow Monumental is a must-read for urban historians and all scholars of the Soviet era."—Heather D. DeHaan, author of Stalinist City Planning: Professionals, Performance, and Power

"Moscow Monumental is a richly researched and expertly crafted book that casts the Stalin era in a new light. Zubovich has written the first history of Moscow's skyscrapers, greatly enhancing our understanding of these monumental buildings and their role in Soviet history."—Steven E. Harris, author of Communism on Tomorrow Street: Mass Housing and Everyday Life after Stalin

"This elegantly written, highly readable, and intellectually engaging work offers a deeper understanding of the multifaceted nature of Stalinism and the legacy of these distinctive Stalinist skyscrapers. Historians and students of every stripe will benefit from Zubovich's exhaustive research and balanced analysis."—Cynthia A. Ruder, author of Building Stalinism: The Moscow Canal and the Creation of Soviet Space

"Moscow Monumental shows how the design, construction, and representation of Stalinist skyscrapers reshaped the urbanism of postwar Moscow. By tracing professional and personal trajectories of Soviet architects, politicians, and elite occupants, but also construction workers, displaced inhabitants, forced laborers, and archaeologists, Katherine Zubovich offers a fascinating view of Moscow from above and from the shadows of the vysotki."—Łukasz Stanek, author of Architecture in Global Socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War