Lost in the Botanical Gardens

Pippa Crawford explores the history of St Petersburg’s hidden green gem

The Palm Greenhouse at the Botanical Gardens. Image source: saint-petersburg.com

‘Where will you go when they let us out?’ a neighbour here in Sussex asked me yesterday. She was only half joking. With more time on my hands than I am used to, I find my mind running back over my last few months in St Petersburg - the places I saw, the people I met there. Today’s destination is the Botanical Gardens of Peter the Great.

Image credit: Pippa Crawford

This is not a place which foists its treasures upon you – more often than not, you have to stumble upon them for yourself. Indeed, it may sometimes require heroic degrees of exertion even to stumble upon them; on the afternoon we visited, my friend Frankie and I spent a good twenty-five minutes wandering around the greenhouses, trying out various doors without making much headway. At last, an elderly gardener spotted us trying to prise our way in, subjected us to a stream of Russian invective, and directed us to a tiny glass entrance, overgrown with ivy and knotted vines. Prepare to be charmed. From outside, the greenhouses loom above the rose gardens, both austere and exuberant in their curved expanses of glass and rusting iron, the misted-up windows spliced at intervals by the shadows of jungle ferns. Inside, steam rises even when the external barometer drops to minus ten or twenty, sub-tropical palms wrestling each other for living space amongst the cacti. Each room is dedicated to the flora of a different continent, each plant labelled and tended with loving precision.

To visit this sanctuary, cross the Karpovka river to Aptekarskii island. As its Russian name suggests, the island was originally home to an apothecary’s garden, where medicinal plants were studied and cultivated. This was during the Enlightenment, when such gardens were all the rage in Europe. Peter the Great could never resist anything European. He founded the gardens in 1714, making them only eleven years younger than the city of Petersburg itself. Originally, nobody was allowed to live on the island except the specialist gardeners. Over the centuries the gardens have grown to fit the changing framework of the times — during the reign of Catherine the First, fruit and vegetables were grown here for the imperial table. In 1823, the gardens became a botanical institute, regularly replenished as returning explorers brought home new specimens — leopard-plants from China and Mongolia, palms and acacias from Brazil, flowering garlic from the Russian Far East.

A “veteran” cactus. Image credit: Noel Kingsbury

At the turn of the century, the gardens housed the second-largest collection of plants in the world, Kew being the largest. The institute was taken over by the Academy of Science in the Soviet era, and was hit especially hard by the war. Ninety percent of the specimens didn’t make it past 1941, and others were badly damaged. Nevertheless, research continues here, and the gardens have endured. As is common in this self-reflective country, the body of remaining specimens has become something of an incidental museum. Some of the plants that survived the war even wear veterans’ medals. Sombre nineteenth-century portraits hang on the walls, and volunteers flit between them, keen to chat about the gardens’ rich history.

Lily-pads in the Orangery. Image credit: Pippa Crawford

The Queen of the Night (Selenicereus grandiflorus) cactus flowering. Image credit: Rich Hoyer/Wikimedia Commons

Of all the rooms, my personal favourite has to be the Orangery. It is enormous and only open in the summer months. Heavy steel lamps are screwed into the ceilings, filling the ponds beneath with light and shadows in a dozen shades of delirious green, and flowers float beside lily-pads the size of Toyota hub-cabs. It gets into your dreams. But the gardens’ most prized specimen — a rare Central American cactus known as the Queen of the Night — is tucked away in Greenhouse Sixteen. The cactus flowers once a year, on a single night in June. On this night the gardens keep their doors open, so staff and guests can toast the happy occasion with champagne.

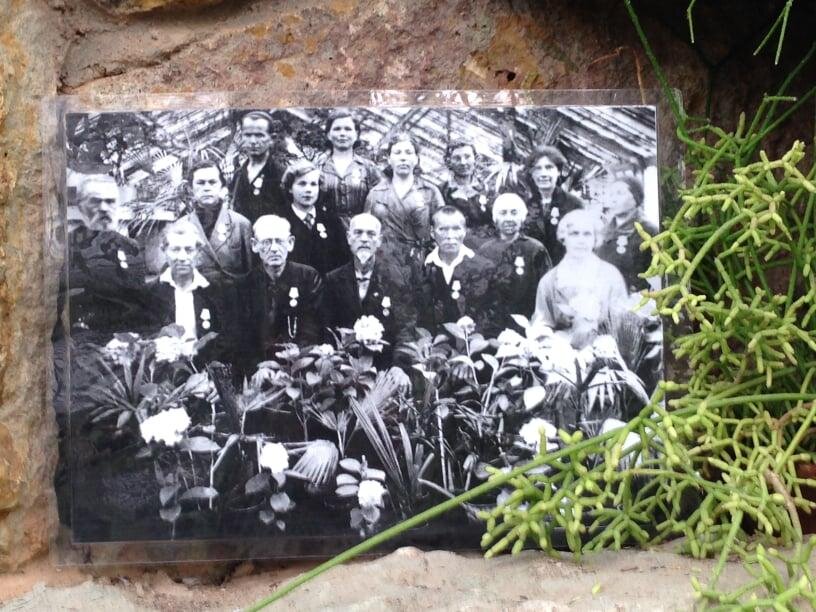

The staff of the Botanical Gardens during the 1940s. Image credit: Pippa Crawford

During my final weeks in Petersburg, locals were comparing the developing virus crisis, again only half in jest, with the 1941 Siege of Leningrad. The siege remains very much in living memory, the city centre still bare where its trees were lopped down as fuel. Over 1.5m people are known to have died. It is not uncommon to run into people whose grandparents survived the era, or to be waylaid on buses by the grandparents and told all about it. The siege holds a particularly poignant significance for the Botanical Gardens and its sister organisation, the Vavilov Institute. Surrounded by irreplaceable seeds, the resident scientists carried job-dedication to its morbid extreme and nine of them starved to death amongst their own specimens. Vavilov himself, having dedicated his life to the alleviation of famine, fell victim to Stalin’s purges and starved in a labour camp. His seed bank, however, survives to this day.

I was touched by this fragile collection of living things, preserved for centuries in an environment which remains conspicuously artificial - and unashamedly urban. We hear so often of the destruction wrought by humanity against the natural world, and not without good reason. Yet we still have places like the Botanical Gardens — painstakingly rebuilt from their own ruins by successive generations, living testaments to our own tenacity. If human care and human ingenuity can shield a palm tree from one hundred and fifty Russian winters, a revolution and two world wars, there is hope for us too — hope for our ability to protect each other — and to protect what we have created, give it space to grow.

I hope to return to Petersburg in time for the flowering of the Queen of the Night. If not, there’s always next year.

Image credit: Pippa Crawford

Pippa Crawford is a freelance critic and student of Russian Studies at University College London. Before the lockdown she was studying at the Higher School of Economics, St. Petersburg. Pippa likes travel and translation and loves drama. She also enjoys watching plays.